Stories: Tay Bak Chiang

(original interview done in Mandarin, translated piece will follow up)

I’ve recorded Bak Chiang’s entire conversation with me on my phone, but it’s been split into two and I’ve accidentally deleted the second segment, scrambling to listen and catch the bus after we’ve wrapped up our chat. I should never have multi-tasked, just as it is pointless to stare at a painting when your head is in the folds of an alternate universe altogether. I should never have tried to entrap a language I sought to demystify, sidestepped as foreign, perching on this risqué reveal like a rumination of love in a diary. But I console myself as rationally as I can. This was why this project even began fruition, if I flail and persevere, that’s persuasion enough for me.

Sentient, Chinese colours and pigments on canvas, 2013.

Soft power. Transference of one reduction to another, till the glass of your mirror is not just magnified like a cleaning ad, but startling in how unembellished we each are as an art. That is poetry, an ecosystem under a rock by the sea. When you lift these rocks, there are organisms underneath, co-existing and bustling beneath these large, looming, grainy exteriors. That’s why I like Bak Chiang’s Stone (2013) series, vivid boulders generous in hues, magnanimous in their strength, offering solace on a canvas that is teeming with life. I’m trying to keep up with him in my broken Mandarin about what I see, but the words flip back down like a turned rock sealing itself back into the sand. The seawater rush of the studio space pools me back to this moment on the couch, Bak Chiang perpendicular on my left, enamel white foam walls tall and poised. There’s a mezzanine which stores his paintings and he smiles while telling me that was his own determinant of success, to have a second level in your studio. The nested paintings look like migratory birds resting after a long flight, tired, hopeful, at peace with transit.

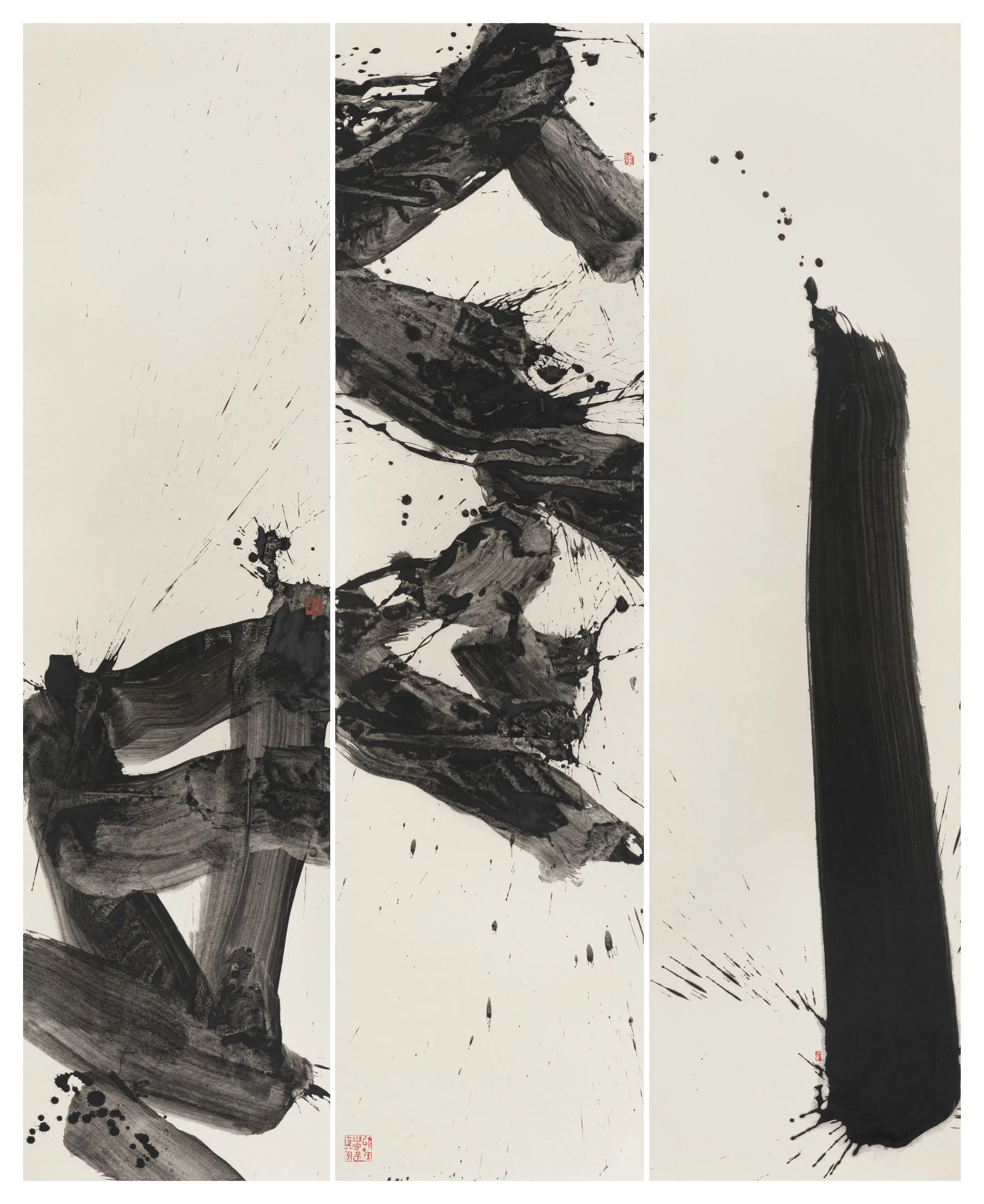

Jiumozhi’s Enlightenment in the Dried-Up Well, Chinese ink and pigments on canvas, 2013.

He had a quiet notion of aging. When I asked him how he began in his practice, he looked at me squarely and said, “Luckily I’m only forty years old. What if I’m eighty?” So he knew that years were residual, even from each reduction, we carry forward particles, invisible like martial art sequences, taut on a surface compelling enough to practice on, be it air, water, paper. I must appear very young to him. I suppose I am.The Breath of a Blade (2012) diced these sequences finely, mincing them without being precious to the remnants of the years. The end result has a stance, seasoned instrument reeds ready to burst into sonnets of a battle. That’s the exhibition he felt most drawn to, it’s an anthem of a finale that can progress to encore.

Lonely Nine Swords Arrangement, Chinese ink and pigments on rice paper, 2012.

He’s resolute in person. He asks me if my favourite colour is blue, and I nod sheepishly. Blue is a shade that is untouched, residing in front of our eyes as nature’s tarp, because blue is the colour that is at core, the base colour for every other colour spectrum we see. I explain that to him, he’s a little sceptical of my meaning (but more amused) now that I’ve suddenly sputtered a long string of Chinese words all hanging on to the lobe like chandelier earrings. He likes blue too. He thinks that blue is evocative, I think he’s seeing people as though they are mists on windows, and whatever is behind that mist is exactly what the colour blue can serve to unveil. It’s a subtle frond, and in art where works are prone to duplication, excess or lacklustre incitement, blue can act as barometer to all these pressures.

Ephemeral, Pigments, chinese ink and colour on rice paper, 2015.

This is the title for this year’s solo at Chan Hampe Galleries, Blue White Vermillion (2015), where I uncomfortably try to mingle, a few days later after our meeting. Bak Chiang is as stoic as ever, everyone is scrambling to get a picture with him, he is happy being a statue for the night. The walls are tinged with blue imagery, the paintings are undaunted settlers after a long hard journey. I’m squeamish as I’m terrible with crowds, so I head outside the gallery space for a breather. Seated on a bench are Bak Chiang’s wife and daughter, both dressed in blue. I introduce myself. They smile like his brush strokes, precise and authentic. They are ardent supporters, it’s the way their eyes are still lit up even when the crowd in the room is too much, so you’re sitting outside waiting to greet your husband and father’s audience. Soft power. Transference of one reduction to another, the bonds between people affirmed by simple actions.

Tay Bak Chiang paints subjects found in the nature of Singapore and Southeast Asia, such as heliconias, lotus ponds and rocks. He aims to reinterpret them inventively in terms of form, composition, technique, material and colour. Lotus flowers, for example, are depicted as minimalist forms in bold hues; lotus stalks as thick, unembellished black strokes; and stones as textured shapes and sculptural blocks in intense colours made by combining pigments and traditional Chinese ink and colours. These subjects, to his mind, are sentient beings that feel and perceive the world around them; he expresses his feelings and philosophies through them. He graduated from the Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts in Singapore in 1995 and studied at the China Academy of Art in Hangzhou, China, in 1997. He was awarded the First Prize in the Chinese Painting category in the 19th and 22nd United Overseas Bank Painting of the Year Competitions (2000 and 2003 respectively). In 2002 he received the Young Artist Award from the National Arts Council of Singapore. He has had ten solo exhibitions to date: Fa Zi Hua Sheng《法自画生》(2003), Between Breaths《呼吸之间》(2010), Ingenuity《天工》(2011), Hear the Wind Sing《且听风吟》(2012), The Breath of A Blade《剑气》(2013), Sentience《顽石》(2014), The Story of the Stone《石头记》(2014), Cleavages Fractures Folds《斧劈皴》(2014) , Blue White Vermilion《青花 • 朱印》 (2015), and The Chivalrous Hero《侠之大者》(2015).

Euginia Tan is VADA’s 2015-2016 Curator. She has published three collections of poetry and is completing her first play. She is interested in the notion of stories (within stories, within stories) and how much of these are lost, or can be resuscitated, when converted into various other multi-disciplinary platforms. Euginia also graduated from Curating Lab 2014.